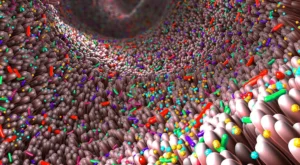

The surface of your body is colonized by a vast population of microorganisms, which is referred to as your skin microbiome. It is estimated that a single square centimeter of skin can contain up to one billion bacteria.

The skin and skin microbiome have many vital functions, including providing a physical barrier that protects against pathogens, regulating temperature, water retention, inflammation, and aspects of the immune system.

Bi-directional communication between the gut and the brain is well documented. Newer studies have now established that the gut and brain also communicate with the skin. This concept was first expressed in 2010 when Dr. Petra Arck proposed a unifying communication system called the Gut-Brain-Skin Axis.i

Each of these organ systems can communicate with each other. For example, it is well known that gut dysbiosis is associated with skin conditions like acne, psoriasis, and eczema.ii Similarly, with psychological stress, the brain can send signals to the skin that promote inflammation.

Skin Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis, (which is also called dysbacteriosis), is a term that indicates an imbalance of bacteria in or on the body. While dysbiosis most commonly refers to a microbial imbalance in the intestinal (GI) tract, it can also denote an imbalance of bacteria on the skin, known as skin dysbiosis.

The gut microbiome is frequently altered in people with skin diseases.iii More recent studies have confirmed that skin dysbiosis is present in skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, acne vulgaris, dandruff, and even skin cancer.iv

This is hardly surprising considering the numerous similarities the gut and skin share. Both act as a barrier between harmful pathogens and the body’s immune system, and when either is compromised—such as when dysbiosis occurs—it can have significant ramifications for your overall health. Since everything in the body is ultimately connected, if something happens in the gut, it can eventually affect your skin, leading to the abovementioned skin conditions.

For instance, if the gut’s microbiome is compromised in such a way that it allows pathogens through the intestinal wall, it can lead to an immune response throughout the body, including at skin level. This in turn may affect the skin’s microbiome as well. Since your diet can affect your gut’s microbial composition, your dermic health could be impacted significantly by what you eat. Likewise, research suggests that it’s possible to mitigate skin conditions by working from the inside out.

Shocking Frequency of Skin Diseases

A large study conducted by the Mayo Clinic between 2005 and 2009 revealed that skin disorders are the most common reasons people visit their doctor.v According to the Mayo Clinic study, 43% of patients made a doctor’s appointment for a skin disorder compared to 33.6% for joint conditions, 23.9% for back problems, 22.4% for cholesterol problems.

Cancer is still the #1 killer in the U.S., nearly half of Americans have high blood pressure, and over one-third of Americans have diabetes or prediabetes. Thus, it was surprising to learn that skin disorders are responsible for more doctor visits than these more common high-profile diseases. The realization that skin diseases are associated with skin dysbiosis emphasizes the importance of maintaining a healthy skin microbiome.

Balance

Most of the bacteria in the gut and on the skin of healthy individuals are beneficial. Balance is the key to both a healthy gut microbiome and a healthy skin microbiome. The gut and skin of all people contain some potentially harmful bacteria. Still, when your microbiomes are predominantly populated with beneficial bacteria, the harmful bacteria cannot multiply and cause problems. Thus, it is essential to realize that skin dysbiosis, like gut dysbiosis, is primarily a microbiome problem being out of balance.

Skin Postbiotic Metabolites

In 2019, an article titled Postbiotic Metabolites: The New Frontier in Microbiome Science explained that probiotic bacteria in the GI tract produce health-regulating compounds we refer to as postbiotic metabolites.vi We are now learning that beneficial bacteria that live on your skin also produce important health-regulating postbiotic metabolites.

One important class of these compounds is called antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Many beneficial skin bacteria strains make various antimicrobial peptides, which suppress the growth of pathogens and accelerate wound healing.vii

Staphylococcus aureus is a strain of bacteria associated with numerous skin diseases such as eczema, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and a high level of S. aureus is an indicator of skin dysbiosis. The skin of healthy individuals contains strains of bacteria that produce AMPs which suppress the growth of S. aureus.viii

A species of skin bacteria named Propionibacterium produces an antimicrobial peptide called Enterocin AS-48. It has been shown to have significant antibacterial activity against 23 different bacteria strains commonly associated with acne.ix

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a beneficial strain of skin bacteria found to produce a postbiotic metabolite named butyric acid. Butyric acid helps to maintain a healthy skin microbiome due to its anti-inflammatory activity.x

In a survey of bacteria isolated from seven body sites, researchers were able to identify 21 different previously unknown postbiotic antimicrobial peptides that exhibited activity against a wide range of skin pathogens.xi

The growing understanding that different species of beneficial skin bacteria produce and secrete postbiotic metabolites that help to maintain a healthy skin microbiome is an exciting new area of science.

The first record of topical probiotic therapy occurred in the Journal of Cutaneous Diseases in 1912, which reported the topical application of Lactobacillus bulgaricus to treat acne.xii However, it would take nearly 100 years before dermatologists understood how beneficial topical probiotics could be to treat skin diseases. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatologists issued a statement calling probiotics a “Beauty Breakthrough.”

Modern topical probiotics can improve the quality and health of your skin by supplying healthy bacteria to your skin’s microbiome. Those bacteria help suppress harmful strains, resulting in improved dermic health. Of course, the right formulation of probiotics and ingredients that help with absorption will have the most optimal results.

Vitamin D and Gut Health

Just as dermic health can be affected by the types of bacteria in your gut, so too could your gut’s health be impacted by your skin. During the summer months, for instance, UV rays can have a dramatic effect on the skin by triggering vitamin D production. Vitamin D has been shown to promote intestinal health, and a vitamin D deficiency could lead to gut dysbiosis, as demonstrated in a recent study in Frontiers in Microbiology. In this study, researchers found that increased exposure to UVB rays had similar effects on microbiome diversity as taking vitamin D supplements.

FAQs on the Gut-Skin Connection

Do probiotics help with skin health?

Probiotics can help support skin health, whether applied topically or taken as a supplement.

Is gut health related to acne? Can probiotics help with acne?

Gut health and acne have been shown to be related. Many studies have indicated that there may be a connection between the bacterial composition in the gut and the prevalence of acne, with acne patients exhibiting a decrease in probiotic species (such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) that normally help balance the gut microbiome and strengthen the intestinal barrier. As such, probiotics can be useful to support healthy skin tissue.

Can gut health affect the skin?

As demonstrated by the numerous studies already cited here, your gut and skin microbiomes work together to build the integrity of your skin.

Can probiotics cause breakouts?

Poor quality probiotics may result in breakouts, and occasionally, you may experience a breakout as your body becomes accustomed to a rebalanced gut or skin microbiome, which could trigger a temporary reaction.

How to Protect Your Skin Microbiome

Here is a list of critical factors that are important for creating and maintaining a healthy skin microbiome:

- Eat a healthy diet: avoid processed foods, minimize sugar, consume a high quantity and diversity of fiber-rich foods.

- Understand that an allergy or sensitivity to food(s) or environmental agent (soap, detergent, household cleaning agent, cosmetics) can cause inflammatory skin diseases.

- Get adequate omega-3 fatty acids in the diet or as nutritional supplements. Omega-3 oils support healthy inflammatory response, fats regulate inflammation, immune function, and overall skin health—recommendation: Dr. Ohhira’s Essential Living Oils™– a vegan form of Omega 3 essential oils balanced with Omega 6 and Omega 9 oils as well .xiii

- Protect skin from excessive exposure to UV light. Dr. Ohhira’s Propolis Plus contains ingredients including that reduce inflammation and astaxanthin, which is a powerful antioxidant that helps to protect protects skin from free radical damage due to UV rays from sunlight.

- Maintain a healthy gut microbiome. Studies have reported a strong link between microbiome imbalances in the gut dysbiosis and various skin concernsinflammatory skin diseases.xiv The gut communicates with the skin via the Gut-Skin Axis. Recommendation: Dr. Ohhira’s Probiotics®

- Read the book Clean: The New Science of Skin by James Hamblin, MD. Dr. Hamblin suggests stopping or dramatically reducing the use of strong chemically-based shampoos, conditioners, and products that damage the skin microbiome. Select natural products that promote skin integrity and a beneficial skin microbiome.

- Use Dr. Ohhira’s skincare products, including Kampuku Beauty Bar, Magoroku Skin Lotion, Hadayubi Lavender Moisturizer, and Collagen Plus. These products contain natural ingredients that help maintain strong collagen fibers and skin elasticity, deodorize and moisturize the skin and add healthy postbiotic metabolites to promote a healthy skin microbiome.

To learn more about ways to protect and balance your skin’s microbiome, contact Essential Formulas.

i Arck P, et al. Is there a ‘gut-brain-skin axis’? Exp Dermatol. 2010 May;19(5):401-405.

ii Salem I, et al. The Gut Microbiome as a Major Regulator of the Gut-Skin Axis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1459.

iii Szanto M, et al. Targeting the gut-skin axis—Probiotics as new tools for skin disorder management? Exp Dermatol. 2019 Nov;28(11):1210-1218.

iv De Pessemier B, et al. Gut-Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions. Microorganisms 2021 Feb 11; 9(2):353.

v St. Sauver JL, et al. Why Patients Visit Their Doctors: Assessing the Most Prevalent Conditions in a Defined American Population. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Jan 1, 2013;88(1):56-67.

vi Pelton R. Postbiotic Metabolites: The New Frontier in Microbiome Science. Townsend Letter. 2019 June;431:61-69.

vii Grice EA and Segre JA. The Skin Microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2011 Apr;9(4):244-53.

viii Ryu S, et al. Colonization and Infection of the Skin by S. aureus: Immune System Evasion and the Response to Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(5):8753-8772.

ix Cebrian R, et al. The potential of bacteriocin AS-48 in the control of Propionibacterium acnes. Scientific Reports. 2018 Aug 6;8(11766.

x Keshari S. et al. Butyric Acid from Probiotic Staphylococcus epidermidis in the Skin Microbiome Down-Regulates the Ultraviolet-Induced Pro-Inflammatory IL-6 Cytokine via Short-Chain Fatty Acid Receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Sep 11;20(18):4477.

xi O’Sullivan JN, et al. Human skin microbiota is a rich source of bacteriocin-producing staphylococci that kill human pathogens. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. Feb 2019;95(2):fiy241.

xii Peyri J: Topical bacteriotherapy of the skin. J Cutaneous Dis. 1912, 30: 688-89.

xiii Balic A, et al. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 23;21(3):741.

xiv Szanto M, et al. Targeting the gut-skin axis-Probiotics as new tools for skin disorder management? Exp Dermatol. 2019 Nov;28(11):1210-1218.