Does the Gut Microbiome Play a Role?

By Ross Pelton, RPh, PhD, CCN

Scientific Director, Essential Formulas

In this article, I will review a classic nutritional study titled: The impact of a low food additive and sucrose diet on academic performance in 803 New York City public schools, published in 1991.i My purpose in reviewing this study is to propose a microbiome-based explanation for the improved academic performance that the children achieved.

Stephen Schoenthaler, Ph.D., obtained funding and permission to improve the quality of food served in the breakfast and lunch meals provided in 803 New York City public schools for four years, from 1979 to 1983. During these four years, over one million children ate either one or two meals a day at school, five days a week.

Measurement of Academic Performance

The California Achievement Test (CAT) is a nationally recognized standardized test that measures achievement in Reading, Language Arts, and Math.ii This test, administered once a year to children in grades K-12, provides educators and parents with a measurement of achievement for a school and individual students, compared to overall national scores.

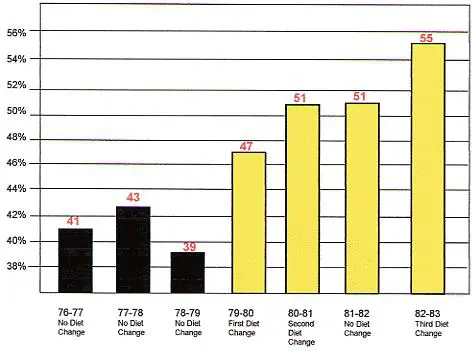

The year before this study began, the New York City schools’ national rank was below the national average at the 39th percentile. And in previous years, the ranking of New York City schools seldom varied more than 1%.

Study Design & Outcomes

- 1979-80: 8.1% higher CAT scores. During the 1979-80 school year, most foods containing significant amounts of sugar and two commonly used food colorings were eliminated and replaced with healthy foods. This change resulted in an average 8.1% increase in the CAT scores in the New York City schools.

- 1980-81: an additional 3.8% increase in CAT scores: during the 1980-81 school year, foods containing the remaining food coloring and flavoring agents were removed from the school meals.

- 1981-82: essentially no change in CAT scores: The investigators maintained the dietary improvements from the first two years this year, but no additional changes were made. As expected, the CAT scores from this year were virtually the same as the previous year.

- 1982-83: an additional 3.7% increase in CAT scores: During this final year of the 4-year study, all foods containing the preservatives BHT and BHA were removed from the school meals, which resulted in a 3.7% improvement in CAT scores over the previous year.

- Results: 15.7% overall gain in CAT scores. Removing foods with high sugar content and synthetic food colorings, flavoring agents, and preservatives and substituting with more fresh vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and non-processed foods enabled over one million kids in 803 New York City schools to elevate their CAT scores from 39.2% at the beginning (below the national average), to 54.9% (above the national average), compared to the rest of the schools in the nation that used the same standardized CAT test. That’s an impressive overall gain of 15.7%. Feeding these kids healthy food enabled them to become more intelligent!

- Result #2: Before this study began, schools with more students eating breakfast and lunch had the lowest CAT scores. At the end of the study, this situation was reversed. The more students who ate meals at school, the higher the school’s CAT scores.

The chart below shows the average of over a million students, but not all children improved the same way. Before the dietary changes, 12.4% of the students were two or more years behind their grades. By the end of the study, only 4.9% of students were below their grade level.

Chart showing NYC schools’ improvements in CAT scores during this study

The Microbiome Perspective

The improvements in students’ academic performance from this study are generally assumed to be related to removing sugar and food additives and eating foods that provide higher levels of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients. I am sure these factors played a role, and I don’t want to minimize their importance. However, I believe essential insights can be gained by considering how improvements in the microbiome may have contributed to the advances in academic performance.

An old saying is that “You are what you eat.” However, it is more accurate to say, “You are what you absorb.” Switching to a healthier diet enhances the growth of beneficial probiotic bacteria and helps create a healthier microbiome ecosystem throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Digestion of food and absorption of nutrients takes place throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Dietary improvements and the resulting improvements in the microbiome can improve digestion and the absorption of nutrients.

For a long time, experts assumed that humans obtained all their nutrients from the foods they consumed. However, it is now understood that numerous nutrients (B vitamins, vitamin K, and amino acids) are postbiotic metabolites produced by probiotic bacteria.

The improvements in food quality enabled the students to consume a greater quantity and diversity of dietary fibers and polyphenols, the primary foods for probiotic bacteria. In addition to promoting the growth of probiotic bacteria, the dietary improvements also enabled the probiotic bacteria to produce a greater quantity and diversity of postbiotic metabolites.

It can be assumed that many students had some degree of dysbiosis and intestinal permeability when this study began. Dysbiosis and intestinal permeability can contribute to brain fog and affect cognitive functioning. When the students started consuming healthier food, the resulting improvements in the microbiome probably helped reduce and/or heal leaky gut, which would also contribute to the students’ gains in academic performance.