Health Benefits of Sulforaphane: A Postbiotic Metabolite with Well Documented Health Results

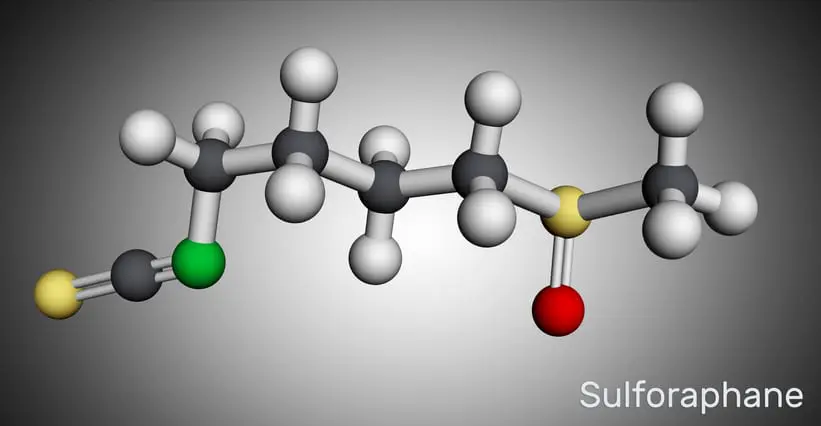

Sulforaphane is a phytochemical that provides powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Numerous studies report that sulforaphane protects against cardiovascular disease, neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, stroke, and multiple types of cancer.i

It is commonly believed that sulforaphane, which belongs to a class of compounds called isothiocyanates, occurs in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, and brussels sprouts. This is a mistake, as these vegetables DO NOT contain sulforaphane. These veggies contain substantial amounts of a sulfur-rich compound named glucoraphanin, which belongs to a class of glucosinolates. When these vegetables are chopped, chewed, or juiced, an enzyme called myrosinase is released, converting the glucoraphanin into sulforaphane. Broccoli sprouts and broccoli seed extract contain the highest amount of glucoraphanin, which can ultimately be converted into sulforaphane.

Cooking Inhibits Sulforaphane Production

Myrosinase enzymes in cruciferous vegetables must be released to convert glucoraphanin into sulforaphane. However, myrosinase enzymes are easily destroyed during storage and by heat. Therefore, cooking methods, including steaming, microwaving, boiling, and stir-frying, destroy the enzymes, preventing sulforaphane formation.ii This is why raw broccoli or lightly steamed broccoli may offer more sulforaphane benefits than cooked broccoli.

Sulforaphane is a Postbiotic Metabolite

Even though storage and/or cooking destroys the myrosinase enzymes, which inhibit sulforaphane production, we have a “back-up” system. It is now known that many strains of probiotic bacteria that inhabit the colon can produce myrosinase, which converts glucoraphanin into sulforaphane. Thus, a significant amount of sulforaphane in humans is a postbiotic metabolite that has been created by probiotic bacteria residing in the colon.iii This highlights the importance of gut health for sulforaphane bioavailability.

This is yet another example that emphasizes that postbiotic metabolites are compounds that regulate and control many aspects of human physiology and health, contributing to various health benefits.